Photographer Jošt Frank has recently published two collaborative newspapers featuring photographs, histories and narratives of people who have left their homes and traversed the Balkan refugee route and managed to reach the European Union.

Both editions, A Memory Without Evidence and Until I Become Home, were created through a series of workshops and dialogues with displaced communities.

“As refugees,” Mohamad Abdul Monaem mentioned during the making of the publication, “We have lost all of our history and documents. And we keep a memory without evidence.”

Challenging the portrayal of refugees as passive victims of decontextualized violence, the newspaper introduces vocal, articulated, and thoughtful deliberations of displaced people.

Both editions include testimonies, articles, poetry, and oral history narratives from the perspective of those who have only recently found their refuge.

Below are excerpts from A Memory Without Evidence and Until I Become Home.

The Feeling of Europe

By Zied Abdellaoui

The feeling of Europe is the feeling of sans-domicile, of being without a home. It is a beautiful place, but I cannot really see it. Because I don’t have the right papers, I don’t really have the right to live ... As if I don’t exist in this world.

There is a big wish in me to erase some hours of the day. I think that is how the homeless start drinking. They want to erase some hours of the day. As for me, I wish to erase those from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m. Because they are very sad hours. I have nothing to do. I can’t do anything, and everything is up to my imagination. In literature, they say, those who have a strong imagination can leave. But our life is a material life. Our history is material history.

After spending three years and eight months on the Balkan refugee route, living in forests and abandoned buildings, the one thing I do not need is more imagination. And so, I wish I had the right to study. The right to work. The right to sleep. And the right to keep on living.

I left Tunisia, my parents — my roots — after the revolution, which I believe has failed. I left Tunisia to finish my own revolution and find my own intellectual body inside myself. But I didn’t find it in Europe: Where is the Europe of luminous ideas?

The authorities say that my journey in Switzerland is provisorisch. Recently, my stay was temporarily extended. I would certainly like to stay in Switzerland, but they make sure to tell us every day, you are not Swiss. Don’t compare yourselves to us, you don’t have the same rights as we do … You know, they tell us the truth. And I need this kind of realism in my life. It’s very dry and very cold, but I need it.

Before I came to Europe, I had faith in a kind of leftist naïveté about human rights.

I believed that all people are born free and equal before the law. But real life is obviously not about human rights, at least not for everyone. When you become mature, you start to understand this. Human rights are a utopian idea. In reality, they are a capricious concept — human rights of some people are worth more than those of others. Life is more complicated than the Geneva Convention. Being a migrant has made me understand this. And so, my future is unclear.

As an asylum seeker, you just stay in the refugee camp, and you wait.

And you eat rice. Rice in the morning, rice for lunch, and rice for dinner. And wait. Wait for one day to be over, wait for another day to start again. Wait for the decision of the administration in charge of your fate. Now I have been waiting for four months: August, September, October, November. Let’s see if December brings a decision. Or maybe January will. Waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting.

Europe has finally killed the revolution inside me.

Zied Abdellaoui is an asylum seeker from Tunisia. He studied political sciences and travelled 4517 kilometres back and forth on the Balkan refugee route before reaching Europe almost four years later.

Dialogue in Room 031

By Soufian Hassan & Mohammed Khan

Je vis dans le camp. C’est très déprimant.

All I want is to sleep.

Il y a un million de personnes ici.

I haven’t slept since I

left Kashmir five years ago.

Les gens vont et viennent.

Just to sleep.

Cela change tous les jours.

This is all I want ...

Seuls quelques-uns y restent.

Just to be able to sleep.

Soufian Hassan is an asylum seeker from Morocco. He spent over a year on the Balkan route. Mohammed Khan is an asylum seeker from Kashmir. He spent a year and a half on the Balkan route.

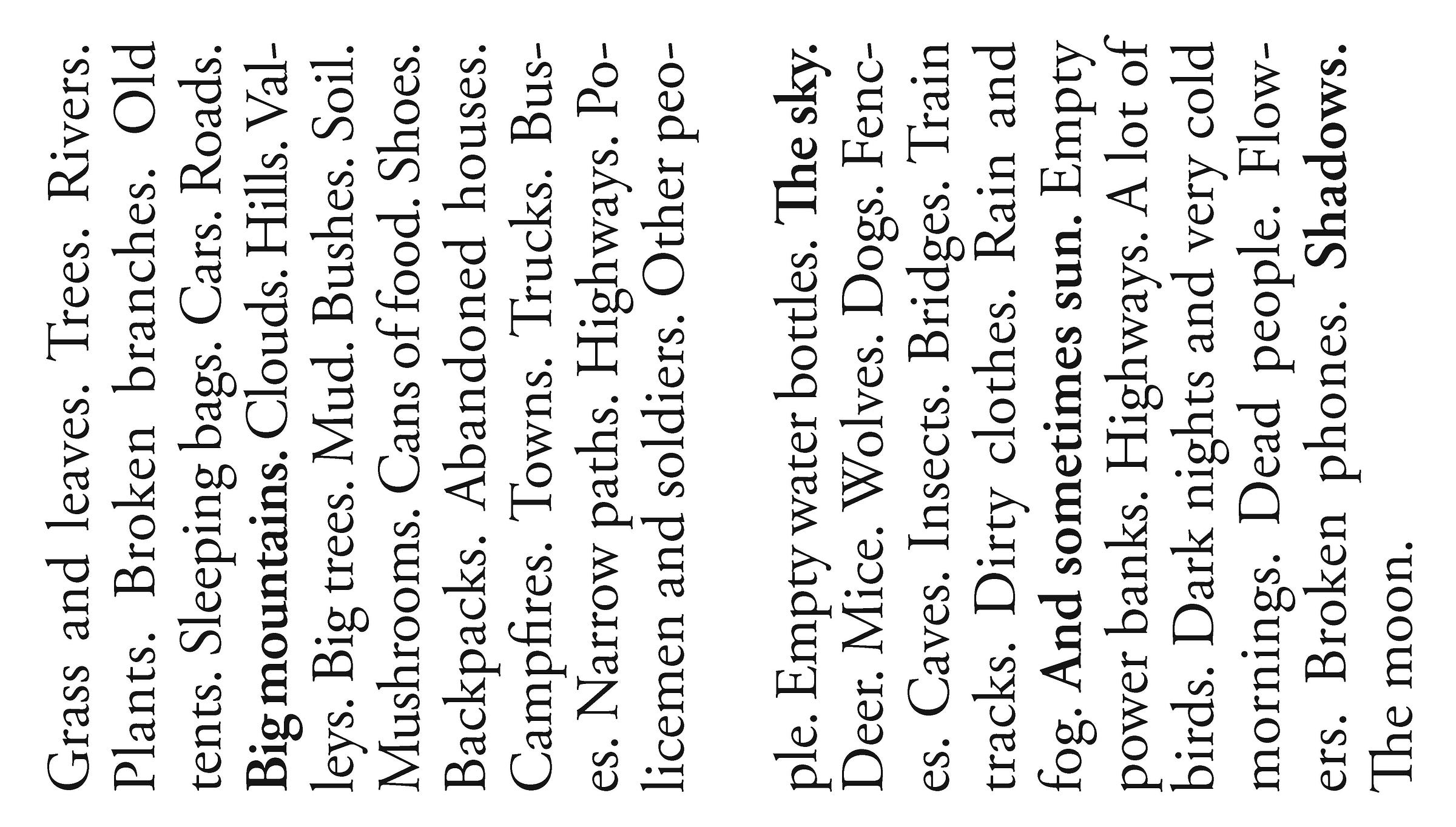

What we see when we walk for days?

By Vahida and Walid*

I Sang at Night So That Birds Could Sleep in My Chest

By Mohamad Abdul Monaem

The Balkans, the ladder of the East... After the rubber boat sank midway between Izmir and Pasas Island in the Aegean Sea, a Turkish rescue ship arrived and threw rope ladders for us to cling to and climb aboard.

Every step I took on this ladder was like reaching the top of Mount Everest.

and then... As I reached the last rung, two strong hands grabbed me under my armpits, pulled me up, and threw me on the ship’s metal deck like a salmon that decided to migrate north and got caught in fishing nets — eyes open to the sky, and below me was a valley at a depth of one thousand five hundred kilometres between Aleppo and Izmir. As for the rest of the fish that were thrown beside me, they probably came from... other places like Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq; people from all over east flee north.

On the steps of the Balkan ladder, I burned my identity step by step, rung by rung, and I threw my memories at the door of the border police after they were done interrogating me. Now at the asylum facility in Ljubljana, I redefine myself every morning and raise the questions of existence once again. But the taste of coffee is not the one I know, and I have no connection to the man who shares the room with me, even though he is Syrian like I am — yet am I really Syrian? — and what is this identity that I’ve escaped from, or the identity that I carry now.

Even though I am Palestinian — still, I do not know Palestine, I was born in Aleppo, without a national card. These days I decided to belong, to love, to give the new place my name and my soul. I loved the Medina River, I loved the old neighbourhood, I likened it to the old Aleppo so that it would be closer to me. I climbed Ljubljana’s castle hill and looked from there for my home as I used to do when I went up to the citadel of Aleppo. I forgot the slow routine that I was waiting for.

To obtain residence and bring my family. Two years had to pass for them to arrive. During that time, I wrote many poems and a novel, and I sang at night so that birds could sleep in my chest.

And I became home, even if only in a dream...

Mohamad Abdul Monaem is a Syrian poet, writer, and publisher of Palestinian origin. After his home in Aleppo was demolished in the civil war, he fled with his family and found refuge in Slovenia.

This project was initiated by Jošt Franko in collaboration with people on the move along the Balkan refugee route between 2020 and 2024.

Jošt Franko is a visual artist and photographer interested in examining long-term and in-depth stories of marginalized groups and individuals. His artistic practice and research is focused on displacement, migrations, workers’ rights and individuals and communities on fringes of society.

You can view more of his work here and here.

Submissions to our Substack are open until August 22. Submit your photography portfolio, a photo series, or writing for a chance to be published. Find out how to submit here.

A wonderfully poignant piece. Really brings the unknown realities of what is happening to the surface. Thank you for posting.

So moving, every word and every image. Each gave me a strong sense of the author and their heartache and their hopes. May they all be allowed to gain safety and security and a sense of belonging - and keep telling us their stories.